Neofolk branches out in such a multitude of sub-genres that there is no singular “scene,” but the bands are bound together by rootedness in folk tradition and its revival from the modern stage. English speaking and Western European acts, defined by bands like Death in June, are often used as the best example of neofolk, but there is a wider musical world focused more concretely on traditional sounds and the use of folk traditions for far more than just nationalist romanticism.

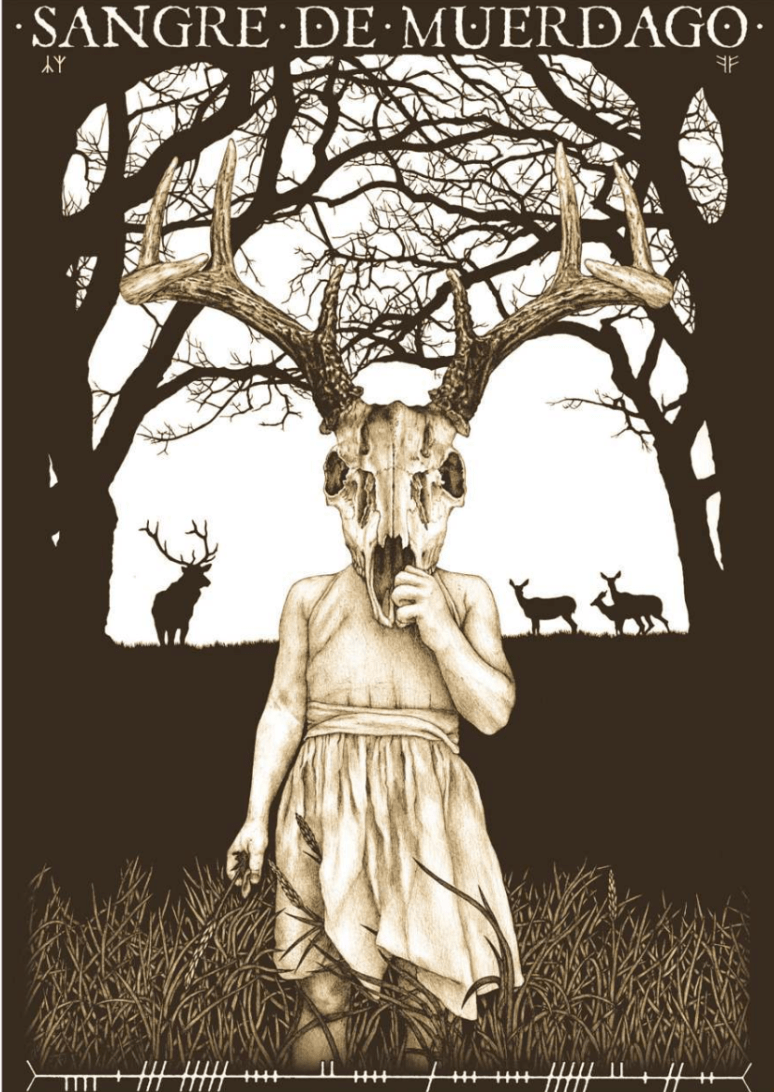

Since we started A Blaze Ansuz, Sangre de Muerdago has been out most requested ban, and their reputation is so large it almost feels insulting to describe them so briefly. A Galician Folk band from Galincia region of Spain, which borders Portugal on the northwest side, Sangre de Muerdago has become a giant of independent neofolk, touring worldwide with their soft brand of regional music that is haunting in its lyrics and acoustic persistence. As a way to counter modern technological society, Sangre de Muerdago revives traditional instruments like classical guitars, nyckelharpa, flute, celtic harp, occasional percussions, into something new and patient, calling back a distant memory of culture based on family bonds and the centrality of the home. Anarcho-punk is where the band finds its roots, they play with those bands often and share members with that scene, and so while they resurrect a very different sound, that anarchistic spirit is on stage with them.

Sangre de Muerdago revolves around front-person Pablo Ursusson, and the band has had shifting line-ups over the years. Each song has such a crafted feel, such quiet love and shifting instrumentation, that it has to be the collective voice of the entire band Sangre de Muerdago, which translates to “Blood of Mistletoe,” is also known for its international appeal, traveling worldwide and collaborating with other artists. This creates a range of venues, from black metal festivals to seated opera halls, and their appeal has gone so far that they are internationally recognized as champions of folk music. Many of their collaborations have become legendary, such as with Tacoma, Washington neofolk band Novemthree, and their genre defining sound has made them the most dependable features of the neofolk scene since their 2007 debut demo.

Their most recent album Noite, released on April 26th of this year, is in full form, calling to a dream of your “true self.” Singing is sparse when there(so is any percussion), and they choose to avoid English in most cases to buck the trend of European neofolk bands appealing to English speaking audiences. Part of this focus on Galician language is a form of cultural resistance to the Franco fascist dictatorship, which limited the language and narrowed its availability.

My reason to speak and sing in Galician is that to sing this music that I write from the depths of my heart, this is the deepest way I can find to feel it is singing Galician. I don’t think I would feel the same way about the songs if I were to sing them in English, or Spanish, for example…The language was very damaged during the dictatorship. Brutally damaged. All the teachers from Galicia were sent to other parts of Spain to teach in Spanish and Castellano. And then they would bring teachers from the south and other parts of the country to teach the Galician kids in Castellano. And all the smaller languages spoken in other areas like Basque, Catalan, or Galician, suffered a lot.

These Galincia poems on love, death, and history draw on that almost lost tradition, and the DIY approach of Sangre de Muerdago is meant to recapture something organic from the community.

The lyrics of Sangre are very melancholic, and they long for something, but they always intend to empower people. It’s not like a desperate cry. We all have sorrow, we all have sadness, but we have to somehow process it, and then make it our fuel. It’s something that keeps my head busy

With this Pablo Urusson acknowledges that Galician music has always been political, a way of using regional autonomy to fight off the forces of the far-right and imperialism. This is similar to the left-wing elements in Catalonia that have resisted both nationalism and the overarching militarism of the Franco dictatorship. They are amazingly open in their support of left-wing revolutionary movements, particularly the struggle against patriarchy,

[F]olk music in Galicia has always been political. Galician folk music became the music of people against the empire and against oppression. For centuries—against the Roman Empire, against the Spanish State, against so many things. So somehow the punks in Galicia are very into folk music.

Galincia’s music didn’t survive without an open revolt, and Sangre de Muerdago is continuing the revival of a tradition that is usually passed between the hands of family members and is alive in the moments when the community finds itself in the relationships it builds;

Lyrically, Sangre de Muerdago is committed to liberation from the mountains of Spain, something they have found in common with other anti-fascist bands like Panopticon and Dawn Ray’d, who they have shared the stage with at places like the Roadburn Festival. When they take the stage the audience drops to silent attention, and a dark oasis is formed where they can finally be vulnerable.

We are putting a few albums by Sangre de Muerdago below and we have added several tracks to our Antifascist Neofolk Spotify playlist and check out the other Bandcamp tracks here.